Exile

Twenty-three years on North Brother Island. Not a prison, technically. Not a sentence, legally. Just a permanent end to the life I had known — administered without trial, without appeal, without mercy, and without end.

Twenty-three years is a long time. It is longer than many people's entire adult lives. It is longer than the period from my birth to my first arrival in a professional kitchen. It is longer than the First World War, the influenza pandemic of 1918, the Roaring Twenties, the crash of 1929, and the first half of the Great Depression — all events that happened beyond the water while I watched the seasons change on thirteen acres of rock and trees in the East River.

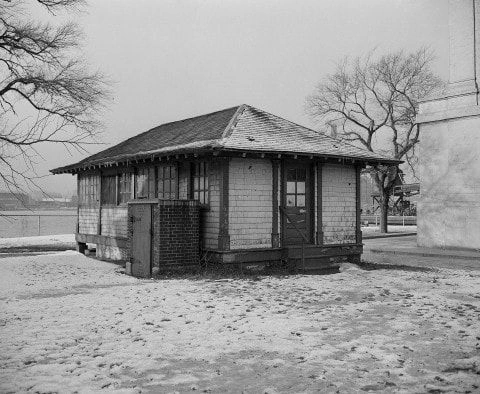

I want to be careful about the nature of my confinement, because inaccuracy would be dishonest, and I have had enough dishonesty applied to my story. I was not in a cell. My accommodation on North Brother Island was a bungalow — small, simply furnished, but a private dwelling. I had freedom of movement on the island itself. I could walk, I could read, I could eventually do some work in the island's laboratory. In the technical language of public health, I was quarantined, not imprisoned.

But let me be equally clear about what quarantine means when it has no defined endpoint and no mechanism of release. It means you cannot leave. It means the decisions about your life are made by people who are not you, based on considerations that are not yours. It means that every morning you wake knowing that today, and tomorrow, and next month, and next year, the view from your window will be the same river, the same hospital buildings, the same narrow strip of land that has become both home and prison.

I spent twenty-three years on that island. Not because I chose to. Not because a judge sentenced me. But because the world decided I was too dangerous to live among them, and no one with the power to change that decision ever chose to use it.

Daily Life on North Brother Island

People rarely ask about the texture of those years — the actual daily existence of a woman confined on an island in the East River. They are interested in the drama: the arrest, the confinement, the injustice. The twenty-three years between those dramatic moments and my death are, in most accounts, summarized in a sentence or two.

The island had a population — medical staff, nurses, other patients and long-term residents. I was not entirely alone, and this mattered. I formed relationships over the years, some of them genuine. The nurses who worked at Riverside Hospital were, in many cases, decent women doing difficult work in an underfunded institution. Some treated me with straightforward professional respect. A few treated me with something warmer than that — a recognition that I was a person, that my circumstances were unusual and unjust, that I deserved to be seen.

I worked in the island's bacteriology laboratory beginning in the late 1910s. The irony was not lost on me, and I did not pretend otherwise. The woman whose bacteria had been at the center of a public health crisis was now helping to analyze bacteria as part of the institution's research work. The laboratory director found me capable and reliable. I learned the work quickly. It gave me something to do with my hands and my mind in the years when cooking was forbidden even here.

Watching the World Change

The world changed enormously between 1915 and 1938. I received newspapers and could follow events beyond the water: the war in Europe and America's eventual entry into it; the explosion of cultural life in the 1920s; the radio, the cinema, the automobile transforming daily existence in ways I could read about but not experience; the crash of 1929 and the suffering that followed; the rise of fascism in Europe and the shadow it cast.

New York changed too. The city I had known as a young woman — crowded, noisy, teeming with immigrant energy and ambition — was becoming something different. The neighborhoods where Irish and Italian and Jewish immigrants had packed themselves into tenements were developing. The social conditions that had shaped my life, while not eliminated, were slowly changing in ways that would eventually produce better protections for workers, women, immigrants.

I watched all of this from a distance of perhaps half a mile of river water. It produced a particular quality of loneliness — not the loneliness of isolation from all human contact, but the loneliness of being separated from the flow of time and change. Of watching life happen while remaining fixed.

The Stroke, and What Followed

In December 1932, I suffered a stroke. I was sixty-three years old. The body that had been my greatest asset — healthy, strong, capable of the sustained physical demands of professional cooking — had begun to fail. I lost movement on my left side. I could no longer walk without assistance. I was moved from my bungalow to a bed in the nurses' pavilion, where I would spend the remaining six years of my life.

The stroke changed things in ways that are difficult to articulate without seeming to demand a sympathy I am not sure I want. I had always defined myself, at least in part, through what my body could do — the work of the kitchen, the endurance of long days and physical labor. To have that capacity diminished in an environment already defined by restriction and limitation was a different kind of loss from all the ones that had come before.

The nurses who cared for me in those final years were largely decent. A few were genuinely kind. I received medical attention — good medical attention, better than I would have received as a poor woman outside the hospital system. I recognize this without gratitude for the system that had put me there, and without pretending that adequate medical care compensates for the loss of freedom that made it necessary.

I died there in 1938, at the age of sixty-nine. I had spent more than half my adult life in isolation. Not because a court had sentenced me. Because the world had decided I was too dangerous to live among them. And no one had ever found that worth challenging.

The Question of Bitterness

People want to know whether I was bitter. Whether I felt the injustice of my situation as a consuming anger that shaped every day of those twenty-three years. The honest answer is: sometimes. Not always, and not as the dominant note of my existence. Bitterness is exhausting, and I had learned early in my life not to spend energy on things I could not change. But yes, there were days — many days — when the gap between what I deserved and what I had received felt like a weight that did not lift.

What sustained me was something harder to name. A stubborn conviction that I had mattered — that the life I had lived before all of this had been real and valuable, even if no one else seemed interested in saying so. That the cook who had produced twenty years of excellent meals for wealthy New York families had existed and had been good at her work and had deserved better. That conviction didn't give me back what I had lost. But it prevented me from losing myself entirely.

I died on November 11, 1938. The cause listed was pneumonia, following the stroke of 1932. I was buried at Saint Raymond's Cemetery in the Bronx, attended by a small group of people who had known me during my island years. The newspapers ran brief notices. Most repeated the familiar story: "Typhoid Mary," the dangerous cook, the cautionary tale, the woman who had refused to cooperate with authorities trying to protect the public.

That story is still the one most people know. This is the one I would have preferred.