My Story

Not the stories they told about me.

Not the rumors that followed me.

Just me, as I lived.

This is my life, told in my own words. Every hardship, every moment of pride, every day I survived. I want you to know me as I truly was — not the myths, not the whispers, but the woman who lived through it all.

The Beginning

1869–1883I was born in Cookstown, County Tyrone in 1869, the daughter of Irish immigrants who had come to America seeking a better life. But better never came — not for them, and not for me.

My mother died when I was still an infant. I have no memory of her face, her voice, or her touch. Only the hollow space where she should have been. My father followed not long after, leaving me alone in a city that cared nothing for orphaned children.

I grew up hungry. Not the kind of hunger you feel before dinner, but the deep, gnawing emptiness that follows you everywhere — when you wake, when you work, when you try to sleep. Poverty was not just the absence of money. It was the absence of hope, of comfort, of anyone who cared whether you lived or died.

But I learned something in those early years. I learned that if I wanted to survive, I would have to be strong. I would have to work harder than anyone else. I would have to prove I was worth something, because the world had already decided I wasn't.

So I worked. I found jobs wherever I could — cleaning, scrubbing, carrying. By fourteen, I was working in kitchens. And that's where I found it: the one thing I was truly good at. The one thing that made me feel like I mattered.

I learned early that the world would not be kind to me. So I learned to be strong instead.

Finding My Craft

1883–1900Cooking. That's what saved me. When I stepped into a kitchen for the first time as a young girl, something inside me shifted. It wasn't just work anymore — it was purpose.

I watched the cooks carefully, memorizing every movement, every technique. I learned how to prepare meals for wealthy families, how to create dishes that brought joy to their tables. And I was good at it. Better than good. I had a natural talent that others noticed.

For the first time in my life, I felt pride. When I made a perfect sauce, when I roasted meat to perfection, when I heard compliments about my cooking — those moments made me forget, if only briefly, that I was an orphan with nothing.

In the kitchen, I was not poor. I was not unwanted. I was a cook — and a skilled one. My hands could create beauty where there had been none. My work mattered. I mattered.

Those years were the happiest of my life, though I didn't know it then. I built a reputation. I earned good wages. I found an identity in my craft that no one could take from me. Or so I thought.

In the kitchen, I was not an orphan. I was not poor. I was a cook — and a good one.

The Life I Built

1900–1906By the turn of the century, I had built something for myself. I worked for wealthy families in their beautiful homes, preparing meals that graced their tables. I commanded good wages — proof that my skills were valued, that I was valuable.

Every morning, I would wake knowing exactly what I was meant to do. Every meal I prepared was an opportunity to prove myself, to create something beautiful with my own hands. The satisfaction I felt when a dish turned out perfectly, when I heard praise for my cooking — those moments sustained me.

I was not rich. I would never be. But I had independence, a rare thing for a woman in my position. I supported myself through my craft. I needed no one's charity. That pride kept me going through long days and exhausting work.

Looking back, those years from 1900 to 1906 were the most stable of my life. I didn't know it then, but I was building toward something — a brief period of contentment before everything changed.

If I could have stayed in that life forever, I would have. But fate had other plans for me.

Every meal I prepared was a small act of defiance. I may have had nothing, but I could create something beautiful.

When Whispers Began

1906–1907It started in 1906, with a family I worked for. People in the household fell ill — not all at once, but one by one. And then, the whispers began. People looked at me differently. They asked questions. They wondered.

I didn't understand. I felt fine. I always felt fine. How could I be the cause of anything when I showed no signs of illness myself? But the suspicions grew, following me from one position to the next.

I lost jobs because of it. Families who had praised my cooking suddenly wanted nothing to do with me. The rumors spread faster than I could move. "Don't hire her," they said. "People get sick when she's around."

Fear and confusion became my constant companions. What had I done? I was just trying to work, to survive. But everywhere I went, misfortune seemed to follow. Or so they said.

I wanted to scream that it wasn't my fault. But no one was listening. They had already made up their minds about me.

They looked at me differently. As if I carried something invisible and dark. But I felt fine — I always felt fine.

The Weight of Misfortune

1907–1915In 1907, a man named George Soper came into my life. He told me I was dangerous. That my very presence could harm others. That I carried something inside me — something I couldn't see or feel — that made people sick.

They forced me into quarantine on North Brother Island. Three years, isolated from everyone and everything I knew. Three years of being told I was a threat to society, despite feeling perfectly healthy. Three years of my life, stolen.

In 1910, they released me under conditions I barely understood. "Don't work with food," they said. "Report regularly to the health department." But how was I supposed to survive? Cooking was all I knew. It was who I was.

I tried to rebuild my life, but the suspicion followed me everywhere. People knew who I was. What I was accused of. Even when I wasn't cooking, even when I was just trying to live, the whispers never stopped.

How do you keep going when the world has decided you're dangerous? When everything you touch is poisoned by fear? I don't know. But somehow, I did.

They told me I was dangerous. That my very presence could harm others. How do you live with that? How do you keep going?

Trying to Survive

1910–1915After my release from North Brother Island in 1910, I tried to follow their rules. I took work as a laundress. The pay was terrible — a fraction of what I had earned as a cook. My hands, once skilled at creating beautiful meals, were now raw and cracked from washing clothes.

Every day felt like a punishment. I had done nothing wrong, yet I was being forced to live a half-life. The one thing I was good at, the one thing that gave me pride and purpose, was forbidden to me.

Financial hardship returned with a vengeance. I could barely afford rent, let alone food. The poverty I thought I had escaped came rushing back. I was drowning, and no one cared.

The desperation was overwhelming. How could they expect me to survive like this? How could they take away my livelihood and expect me to simply accept it? I had committed no crime. I had hurt no one intentionally. Yet I was being treated as if I had.

They took away the one thing I was good at. The one thing that made me feel like I mattered. And I was expected to just... accept it.

They took away the one thing I was good at. The one thing that made me feel like I mattered.

The Return

1915In 1915, I made a choice that would seal my fate. I returned to cooking. I used a different name and took a position at Sloane Maternity Hospital. It was the only way I could survive.

For a brief time, I felt like myself again. I was back in a kitchen, doing the work I loved. The work that defined me. I was no longer drowning in poverty. I had dignity again.

But it didn't last. Another outbreak occurred at the hospital. Twenty-five people fell ill. Two died. And they traced it back to me. They arrested me again, and this time, I knew there would be no release. No second chance.

They called it defiance. Recklessness. They said I knew what I was doing, that I had willfully endangered others. But they didn't understand. I didn't understand. How could I knowingly harm people when I felt perfectly fine? When I had no symptoms, no illness?

I went back to cooking because it was all I had. It was who I was. Without it, I was nothing. And they punished me for trying to survive.

I went back to cooking because it was all I had. It was who I was. Without it, I was nothing.

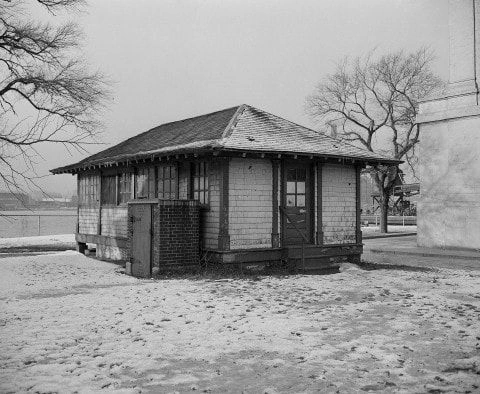

Exile

1915–1938They sent me back to North Brother Island in 1915. This time, I would never leave. Twenty-three years. That's how long I spent in isolation, cut off from the world, from life, from everything that made me human.

I worked in the island's laboratory — a cruel irony. The woman accused of spreading disease was now surrounded by it every day. I had visitors, but they were few and far between. Most days, I was alone with my thoughts and my regrets.

In 1932, I suffered a stroke. My body, which had been so healthy for so long, finally began to fail. I could no longer move as I once did. I was trapped not just on the island, but in my own failing body.

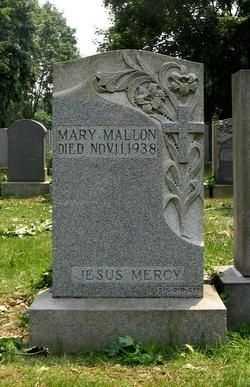

I died there in 1938, at the age of sixty-nine. I had spent more than half my life isolated, punished for something I never fully understood. I died largely forgotten by a world that had turned me into a monster.

Twenty-three years alone. Not because I chose to. But because the world decided I was too dangerous to live among them.

I spent twenty-three years alone. Not because I chose to. But because the world decided I was too dangerous to live among them.

What They Never Told You

The TruthThe stories you've heard about me are wrong. Not just a little wrong — profoundly, harmfully wrong. They made me into a monster, a cautionary tale, a villain. But I was none of those things. I was a woman trying to survive.

The death toll attributed to me has been wildly exaggerated. Reports often claim I caused fifty or more deaths. The truth? Around fifty-one confirmed infections, approximately three deaths. Many cases blamed on me were never proven to be connected. But the myth grew, and no one bothered to correct it.

I contracted typhoid fever once in my life. I recovered quickly. I had no idea I was still carrying the bacteria. Asymptomatic carriers were barely understood by medical science at the time. How could I knowingly harm people when I didn't even know such a thing was possible?

Other typhoid carriers existed during my lifetime. Many of them. But they weren't quarantined for life. They weren't vilified in the press. They weren't turned into nicknames and cautionary tales. Why was I treated differently? Because I was poor. Because I was a woman. Because I was Irish. Because I was convenient.

They made me a monster. A cautionary tale. A nickname. But I was always just Mary.

They made me a monster. A cautionary tale. A nickname. But I was always just Mary.

Who I Really Was

I was a skilled cook who took pride in my work. An immigrant who survived poverty and loss. A woman who faced injustice but never stopped trying. Someone who deserved dignity but was denied it. A human being, not a cautionary tale.

This is my story. Not the one they told. The one I lived.