What They Never Told You

The stories you've heard about me are wrong. Not just a little wrong — profoundly, harmfully wrong. They made me into a monster, a cautionary tale, a villain. But I was none of those things. I was a woman trying to survive.

Let me start with the most fundamental lie: the death toll. You've probably heard that I killed fifty people, maybe more. Some accounts claim dozens of deaths across New York. The newspapers loved to inflate the numbers, each retelling adding a few more victims to my supposed count. The truth? Around fifty-one confirmed infections directly linked to me. Approximately three deaths that can be reasonably attributed to those infections.

Three deaths is still three too many. I'm not minimizing that. But there's a vast difference between three and fifty. Between being someone who unknowingly transmitted disease and being a mass murderer. The newspapers never bothered with that distinction.

They needed a villain, and I was convenient: Irish, female, poor, working-class. The perfect scapegoat for public health failures they didn't want to acknowledge.

Many of the cases blamed on me were never proven to be connected. George Soper, the sanitary engineer who first tracked me down, made assumptions based on circumstantial evidence and speculation. He visited households where I had worked, found evidence of typhoid cases, and concluded I must have been responsible. No rigorous testing. No scientific verification. Just assumptions that confirmed his theory.

Some of those households had typhoid cases before I arrived. Some had cases after I left. Some had multiple possible sources of infection — contaminated water, other carriers, poor sanitation. But Soper had his theory, and confirming it meant advancing his career. Questioning it meant admitting uncertainty. Which do you think he chose?

The Lie of Deliberate Harm

The second major lie: that I knew I was a carrier and deliberately spread disease anyway. This narrative has become so ingrained in popular culture that it's treated as established fact. "Typhoid Mary," the selfish woman who refused to stop cooking despite knowing she was dangerous. The truth is more complicated and considerably less villainous.

I contracted typhoid fever once in my life, probably as a teenager in Ireland. The illness was brief, and I recovered quickly. I had no idea I was still carrying the bacteria. Why would I? The concept of "healthy carriers" was virtually unknown in 1906. Even medical professionals were skeptical. The idea that someone could spread disease while feeling perfectly healthy contradicted everything medicine believed about how illness worked.

When Soper first approached me with his theory, I thought he was insane. Some stranger telling me I was spreading deadly disease despite feeling healthy? It sounded like superstition, not science. I refused his demands for testing because they seemed based on nothing more than wild speculation. Would you submit to invasive medical procedures based on a stranger's unproven theory about you?

Even after the tests confirmed I was a carrier, I struggled to understand how that was possible. How could I be dangerous when I felt fine? How could preparing food — something I had done skillfully for years — suddenly become a threat? The science was too new, too counterintuitive, too easily dismissed as medical overreach.

And here's what history rarely mentions: I wasn't defiant out of malice or selfishness. I was terrified. They were telling me my livelihood — the one skill I had developed, the only way I knew how to support myself — was now impossible. They were saying I could never work as a cook again, which meant I would have no way to earn a living. No safety net. No alternatives. Just poverty and dependence.

The Double Standard

The third and perhaps most galling lie: that I was uniquely dangerous, that quarantining me for life was necessary for public health. I was not the only typhoid carrier in New York. Not even close. Health authorities identified hundreds of other carriers during the same period. Many of them were male. Many were wealthier than I was. Many worked in food service or other occupations where they could potentially spread disease.

None of them were quarantined for life. None of them became household names synonymous with pestilence and death. None of them lost their freedom for decades. Why was I different?

I was poor. I was Irish. I was a woman. I was convenient. The authorities needed to demonstrate they were taking public health seriously, and sacrificing one immigrant cook was an acceptable price for that demonstration.

Consider Tony Labella, a male carrier identified around the same time I was. He infected 122 people and caused five deaths — far more than were ever definitively linked to me. He was asked to check in with health authorities periodically. That was it. No forced quarantine. No lifetime imprisonment. No nickname turning him into a cultural symbol of contagion.

Or Alphonse Cotils, a restaurant and bakery owner who infected at least 30 people. He was told to stop handling food and find other work. He was monitored, but he remained free. He could change careers, find new employment, live his life. I was given no such options.

The pattern is clear when you actually look at the historical record. Male carriers were given guidance and supervision. Female carriers, particularly working-class immigrant women, were subjected to far harsher measures. I was the most extreme example, but I wasn't an anomaly. I was part of a pattern of gendered, class-based public health enforcement that historians have documented extensively — though somehow that context rarely makes it into popular retellings of my story.

The Myth of Defiance

They say I was defiant. Uncooperative. Refusing to follow reasonable public health measures. The reality is more nuanced. Yes, I returned to cooking after my first release in 1910. But what were my alternatives?

The health department offered me a job doing laundry at $20 per month. As a skilled cook, I had been earning $40-50 per month. They were asking me to accept a 60% pay cut for work that would barely cover rent and food, let alone allow me to save anything or maintain any quality of life. And this was supposed to be a "reasonable" solution?

I tried to find other work. I looked for positions that didn't involve food preparation. But I was "Typhoid Mary" now. Newspapers had published my name and photograph. Everyone knew who I was. Employers saw me as a liability, a risk, a problem. Even jobs unrelated to cooking were closed to me because of my notoriety.

So yes, I eventually returned to cooking, using a false name to avoid detection. I didn't do it out of vindictiveness or disregard for public health. I did it because I needed to survive, and every legitimate avenue had been closed to me. When the choice is between poverty and using the only skill you have, what would you do?

They wanted me to choose between my survival and their safety. Then they vilified me for choosing survival. As if any of them wouldn't have done the same.

And here's another uncomfortable truth: during my five years of freedom between 1910 and 1915, there's no documented proof that I caused any new infections. The 1915 outbreak at Sloane Maternity Hospital that led to my second arrest is the only case linked to me during that period, and even that connection has been questioned by some historians. Twenty-five people fell ill. Two died. Terrible, yes. But was I definitely the source?

The hospital had other potential vectors of infection. The water supply was suspect. Other staff members could have been carriers. But I was already a known carrier with a documented history, so of course I was blamed. The investigation that followed my arrest was cursory at best. They had their prime suspect, and that was enough.

What Could Have Been Different

Imagine if the health department had approached me differently from the beginning. Not as a criminal to be apprehended, but as someone who needed help understanding a new and frightening medical reality. Imagine if they had offered me:

Education about asymptomatic carriers, explained clearly and without condescension. Financial support during the transition to new employment, not a poverty-wage laundry job. Job training for careers that didn't involve food handling. Assistance finding housing and employment with employers who understood my situation. Regular medical monitoring without the threat of imprisonment.

These weren't impossible demands. Some of these measures were eventually implemented for other carriers. But I was the first, the test case, and they chose coercion over cooperation. They chose publicity over privacy. They chose punishment over support.

Even the quarantine itself could have been different. I wasn't infectious through casual contact. I posed a risk specifically through food preparation. Isolation on an island for 26 years was medically unnecessary — it was performative public health, demonstrating government authority at the expense of one woman's freedom.

Other countries managing typhoid carriers during the same period used less draconian measures. Regular testing and monitoring. Restrictions on specific types of work. Education about hygiene. Support for career transitions. These approaches worked. They protected public health without destroying individual lives. But New York chose a different path with me, and once that precedent was set, reversing it would have required admitting they had been wrong. That admission never came.

The Legacy of "Typhoid Mary"

My name became shorthand for someone who spreads harm while refusing to acknowledge it. "Don't be a Typhoid Mary" means don't be selfish, don't be willfully ignorant, don't put others at risk out of stubborn defiance. The phrase has outlived me, becoming part of common language, used in contexts far removed from its origin.

But that legacy is built on lies and oversimplifications. I wasn't defiant — I was desperate. I wasn't ignorant — I was dealing with brand-new science that even doctors struggled to understand. I wasn't selfish — I was trying to survive in a system designed to keep people like me poor and powerless.

The real lesson of my story isn't about individual responsibility or public health compliance. It's about what happens when authorities prioritize punishment over support, publicity over privacy, and coercion over cooperation. It's about how class, gender, and ethnicity shape who gets blamed and who gets help. It's about the human cost of making examples of people.

They made me a monster so they wouldn't have to confront the monstrous system that created my situation. It was easier to blame one Irish cook than to examine why poor immigrants had so few options, why women's labor was so devalued, why public health policy prioritized control over care.

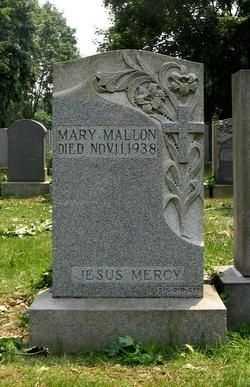

I died in 1938, still quarantined on North Brother Island. I was 69 years old. I had spent more than half my adult life in isolation. No trial. No sentence with a defined endpoint. No possibility of appeal. Just decades of captivity for the crime of being infected with bacteria I didn't know I carried.

An autopsy after my death confirmed the presence of typhoid bacteria in my gallbladder. The doctors were right about the basic science. But being right about the medical facts doesn't make them right about how they treated me. Science might have identified me as a carrier, but politics and prejudice determined my punishment.

The Truth They Never Told You

So here's what they never told you about "Typhoid Mary":

I didn't kill fifty people. I likely caused three deaths — three too many, but nowhere near the dozens often claimed. I didn't know I was a carrier until authorities told me, and even then, the science was too new for me to fully comprehend. I didn't return to cooking out of malice but out of desperation, after being denied any realistic alternative means of supporting myself.

I wasn't uniquely dangerous. Hundreds of other carriers existed, many of whom infected more people than I did. None of them received the same treatment. I wasn't the villain of this story. I was a woman caught in impossible circumstances, punished for poverty and ethnic background as much as for any actual public health risk.

The real story isn't about a dangerous woman refusing to cooperate with reasonable authorities. It's about authorities using one woman as a scapegoat for systemic failures. It's about what happens when public health becomes performative rather than pragmatic. It's about who gets blamed and who gets forgotten.

My name lives on, but the truth of my life was buried long before I died. I'm telling you now, in my own words: I was not the monster they made me out to be. I was just Mary. And I deserved better.