When Whispers Began

The summer of 1906 changed everything. One family's illness became my nightmare, setting in motion events that would define the rest of my life.

The summer house in Oyster Bay was beautiful — one of those grand estates overlooking Long Island Sound, where wealthy families escaped the heat of New York City. I had worked in dozens of homes like it before. Clean kitchens, modern appliances, generous pay. The Warren family seemed pleasant enough. I had no reason to think this job would be any different from the others.

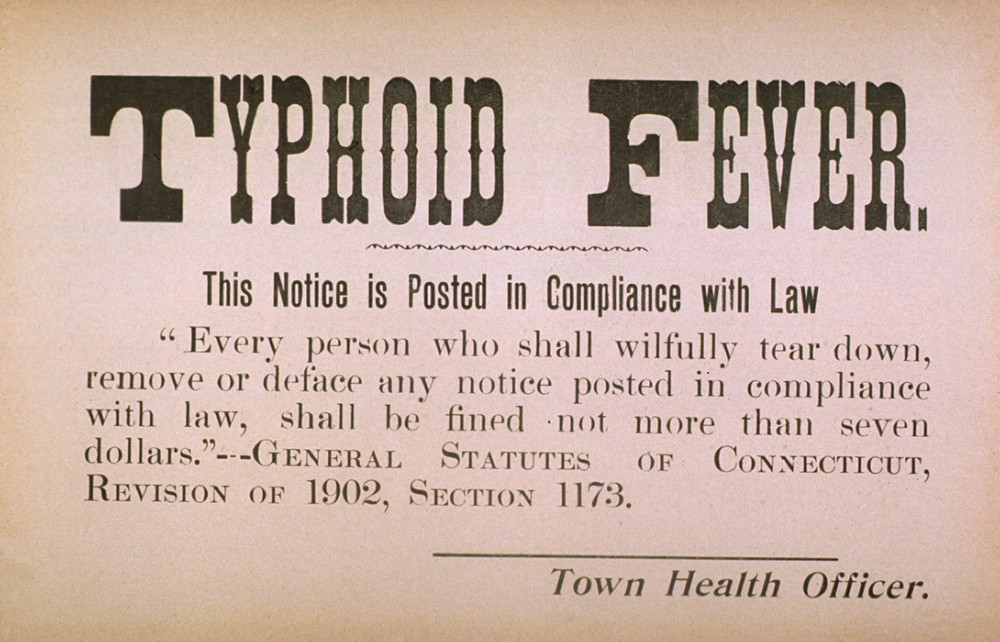

But within days of my arrival, something changed. The youngest daughter fell ill first — fever, weakness, stomach pain. Then her sister. Then Mrs. Warren herself. The doctor was called, tests were run, and the diagnosis came back: typhoid fever.

Typhoid was a terrifying word in 1906. It conjured images of overcrowded tenements, contaminated water, immigrant neighborhoods. Not wealthy summer estates with modern plumbing. The Warrens were shocked. How could this happen here? Who was responsible?

I kept working, of course. What else could I do? The family needed meals, and I needed the wages. But I noticed the way the household staff began looking at me. Whispers in hallways. Doors closing when I approached. Someone had started connecting dots that shouldn't have been connected.

I had no idea I was carrying death in my hands. How could I? I felt perfectly healthy. I had never been sick a day in my life.

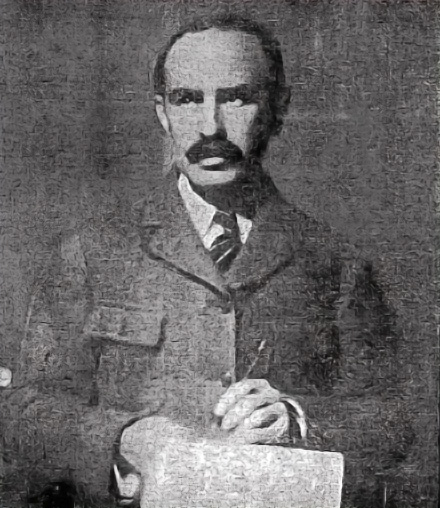

George Soper arrived a few weeks later. He was a sanitary engineer hired by the Warrens to investigate the outbreak. Professional, methodical, certain he would find the source. He examined the water supply, the milk, the ice cream. Nothing. Every test came back clean.

Then he turned his attention to me.

The Investigation Begins

Soper's theory was unprecedented: I was a "healthy carrier" of typhoid fever. I had contracted the disease at some point, recovered without knowing I had it, and now carried the bacteria in my body without any symptoms. Every meal I prepared, every dish I touched, could potentially spread the infection.

It sounded absurd. I felt perfectly healthy. I had no fever, no weakness, no symptoms whatsoever. How could I be spreading disease? But Soper was convinced. He began tracing my employment history, visiting every household where I had worked over the past several years.

The pattern he claimed to find was damning: typhoid outbreaks followed me wherever I went. Seven families. Twenty-two people ill. One death. All connected to the places I had cooked. The coincidences, he insisted, were too many to ignore.

I refused to believe him. Why should I? Some stranger comes into my life, making wild accusations based on circumstantial evidence, demanding that I submit to invasive medical tests. No formal charges, no legal authority, just a man with a theory and the assumption that I would cooperate.

Forced Compliance

When I refused Soper's demands for testing, he went to the authorities. Dr. Sara Josephine Baker, a city health inspector, was sent to convince me. I was working at a new household by then, and I remember the day she arrived with police officers — as if I were some kind of criminal.

I ran. What else was I supposed to do? Let them drag me away based on accusations I didn't understand? They found me hiding in a closet hours later. Five police officers to subdue one Irish cook. They forced me into an ambulance and took me to Willard Parker Hospital.

The tests confirmed Soper's theory. I was carrying Salmonella typhi in my gallbladder, shedding bacteria even though I felt perfectly healthy. The medical establishment had their proof. I had become the first documented "healthy carrier" of typhoid fever in America.

They treated me like a medical curiosity, not a person. I was "Typhoid Mary" now — no longer Mary Mallon, no longer a skilled cook, no longer even quite human in their eyes.

Everything changed that summer. I didn't know it yet, but my life as a free woman was effectively over. The whispers had begun, and they would follow me for the rest of my days.