The Weight of Misfortune

In 1907, a man named George Soper arrived at my employer's home and told me I was dangerous. That my very presence could harm others. I thought he was insane. Within weeks, I was imprisoned on an island in the East River — without a trial, without a lawyer, without a charge.

George Soper was a sanitary engineer. Not a doctor. Not a public health official with legal authority to order my confinement. A sanitary engineer who had been hired by a wealthy family to investigate a typhoid outbreak at their summer home in Oyster Bay, Long Island. He had traced the cases — in his estimation — to the family's cook. To me.

He came to my current employer's home in the winter of 1907. I was preparing a meal when he arrived and asked to speak with me. He explained his theory: that I was a "healthy carrier" of typhoid bacteria — a person who harbored the disease without showing symptoms, and could transmit it to others through food preparation. He wanted samples. Blood. Urine. Stool. He wanted to test his hypothesis.

I threw him out. I don't apologize for that, and I never have. A stranger appeared at my workplace with an accusation that made no scientific sense to me — I had never been seriously ill, I had never seen evidence that anyone became sick because of my cooking — and demanded that I submit to invasive testing based on nothing but his theory. What would you have done?

They told me I was dangerous. That my very presence could harm others. How do you live with that? How do you keep going when the world has decided what you are before you've had a chance to speak?

Soper came back. Twice, three times. Then he involved the New York City Department of Health. On March 19, 1907, a team of health workers arrived at my employer's home with police officers in support. They physically forced me — I resisted, and I was not gentle about it — into an ambulance and transported me to Willard Parker Hospital. I was then transferred to a bungalow on North Brother Island, in the East River, which had been used to quarantine patients with infectious diseases.

No Trial. No Charge. No End Date.

Let me be precise about what happened to me, because the precision matters. I was not arrested. There was no criminal charge. I had no trial. No judge heard my case and sentenced me to a period of confinement. No lawyer represented my interests. No one explained to me, in terms I could verify, what legal authority permitted the city to confine me against my will.

I was simply taken. By force. And held. With no defined endpoint, no clear process for release, no established rights as a person in confinement. The health authorities were operating under broad public health powers that had never been tested in exactly this way — using quarantine not to isolate someone who was actively ill, but to permanently remove a healthy person from public life on the grounds that they might, under certain circumstances, make others sick.

I spent three years on North Brother Island. From March 1907 to February 1910. I want you to understand what three years of involuntary isolation means. It means watching seasons change from the same small strip of land, surrounded by water, with no ability to leave. It means interacting primarily with health workers and hospital staff, not because you are sick, but because the government has decided you are dangerous. It means losing your work, your income, your routines, your relationships — everything that constitutes a life.

North Brother Island

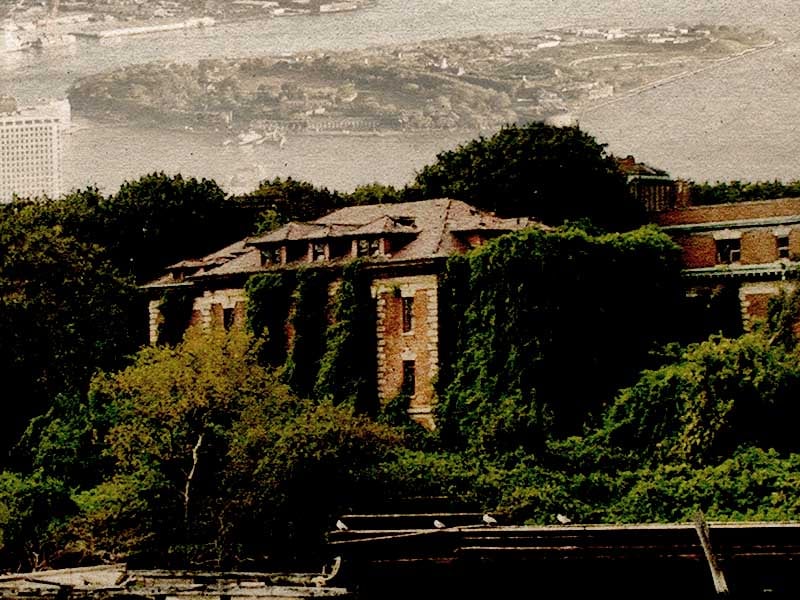

North Brother Island sits in the East River between the South Bronx and Rikers Island. It is perhaps thirteen acres — a small, isolated strip of land that had been used as a quarantine facility since the late nineteenth century. The General Slocum disaster of 1904, in which more than a thousand people died in a steamboat fire, had brought North Brother Island its most terrible moment of visibility. By the time I arrived, it housed Riverside Hospital, a facility for patients with infectious diseases, and various staff quarters and auxiliary buildings.

My accommodation was a small bungalow near the hospital. Not a prison cell — I want to be accurate — but a cottage of isolation, surrounded by water, under the supervision of health authorities who could enter whenever they wished. I had some freedom of movement on the island itself, within the limits they set. I could walk. I could read. I could, with supervision, occasionally interact with the island's population of patients and staff.

What I could not do was leave. What I could not do was return to my work, my home, my companion, my life. What I could not do was exercise any meaningful control over my own existence. I was, in every practical sense, a prisoner — regardless of what terminology the health authorities used to describe my situation.

Fighting Back

I did not accept my confinement quietly. I want that on the record. I sought help from anyone who might be able to assist me — journalists, lawyers, sympathetic members of the public who wrote letters to newspapers on my behalf. In 1909, with the assistance of a lawyer named George Francis O'Neill, I filed a writ of habeas corpus challenging the legality of my detention.

The newspapers had discovered me by then. Some covered my legal challenge with sympathy — here was a woman imprisoned without trial, denied the most basic legal protections, held indefinitely by government authorities on the basis of an unproven medical theory. Others used the opportunity to paint me as a monster: "Typhoid Mary," the dangerous Irish cook who refused to cooperate with the health authorities trying to protect the public.

The court ruled against me. Justice Mitchell Erlanger of the New York Supreme Court found that the health department had acted within its authority, that the medical evidence justified my confinement, and that the public health interest outweighed my individual liberty. I was not surprised. I was an Irish immigrant woman without money or connections. The law was not designed to protect people like me from the people who had imprisoned me.

How do you keep going when the world has decided you're dangerous? When everything you touch is poisoned by fear? I don't know the answer. But somehow, I did. The anger helped. The determination to be seen as something more than a vector helped. The simple refusal to disappear helped.

Release, and Its Conditions

In February 1910, the new Commissioner of Health, Dr. Ernst Lederle, agreed to release me under conditions. I was to report to health authorities regularly. I was never to work as a cook. I was never to handle food for others. In exchange for these restrictions — which amounted to the permanent elimination of my livelihood — I was given my freedom.

I accepted. I had no choice. Three years on North Brother Island had taught me that fighting the system directly produced only defeat. I signed what they put in front of me and I left.

But understand what I had signed. I had signed away the only profession I had ever known. The work that gave me income, identity, and independence. The skill I had spent twenty years developing. In exchange for my physical freedom, I had agreed to become someone with no viable means of supporting herself in a city that was already disposed to treat women of my class and background as invisible and expendable.

I was released into a city that had already decided who I was. The newspapers had seen to that. "Typhoid Mary" was a name, a story, a warning. The woman behind it — her twenty years of skilled work, her hard-won independence, her humanity — had been buried under the myth before I ever got off that island.